Secrets to Corona Treatment for Flex-Pack Films

Corona treatment is an essential process used in the flexible packaging industry to improve adhesion on low surface energy polymers. This paper explores how corona treatment prepares polymers for adhesion, how surface energy correlates to a good bond, forms of measurement, and common pitfalls to avoid. By understanding the function of corona treatment and the science of the bond, converters can achieve consistent adhesion in printing, coating, and laminating applications.

Functions of Corona Treatment

Corona treatment is used for non-polar, low surface-energy substrates like polyethylene and polypropylene. Before corona treatment, these substrates repel inks, coatings, and adhesives – resulting in poor wetting and poor adhesion. Corona treatment solves this problem by introducing polar functional groups onto the surface of these substrates – increasing their surface energy and improving wettability and printability [5][10]. Inside the corona discharge, high-energy species break molecular bonds and form free radicals [10]. The free radicals rapidly react with atmospheric oxygen to add the polar groups onto the surface.

Types of Corona Treaters

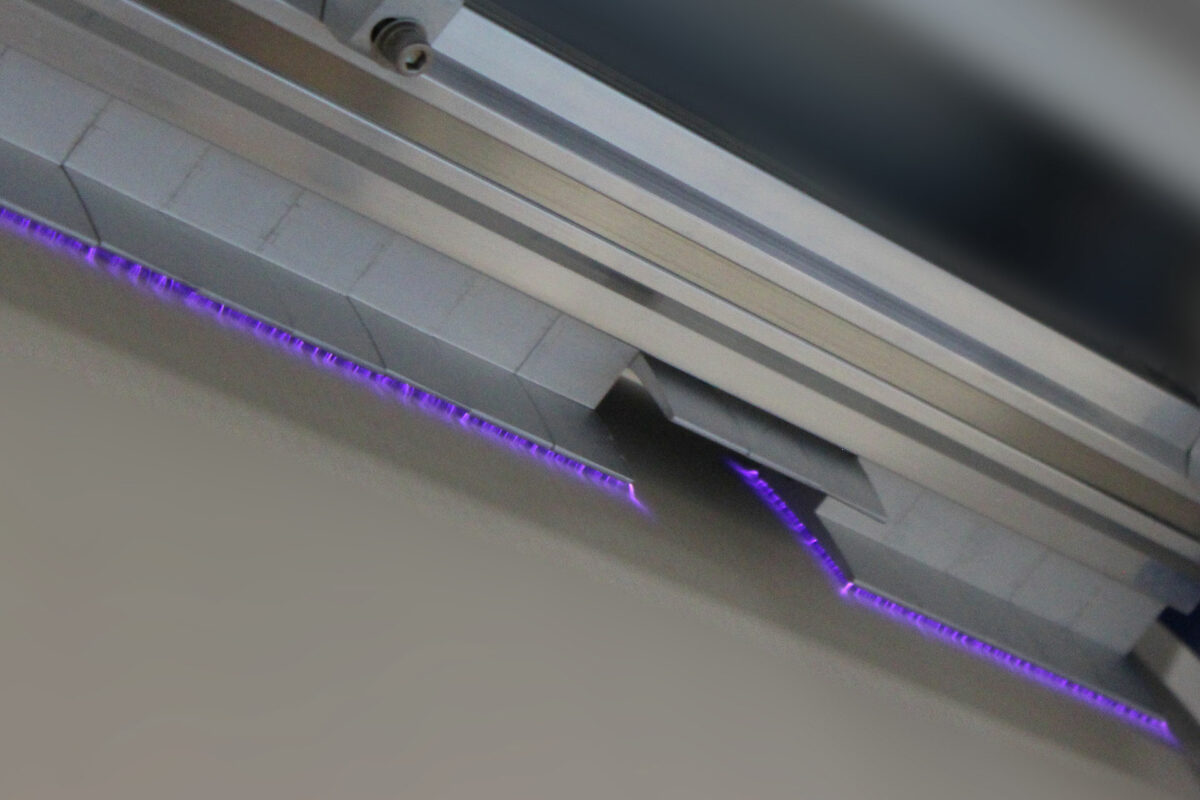

There are two common types of corona treaters. A covered roll corona treater features a covered ground roll paired with an aluminum electrode (for blown film and nonconductive substrates), and a bare roll corona treater features a bare ground roll paired with a ceramic electrode. There are more than just these two configurations, but these two are the most common and cover most standard applications.

Key Components of a Corona Treater

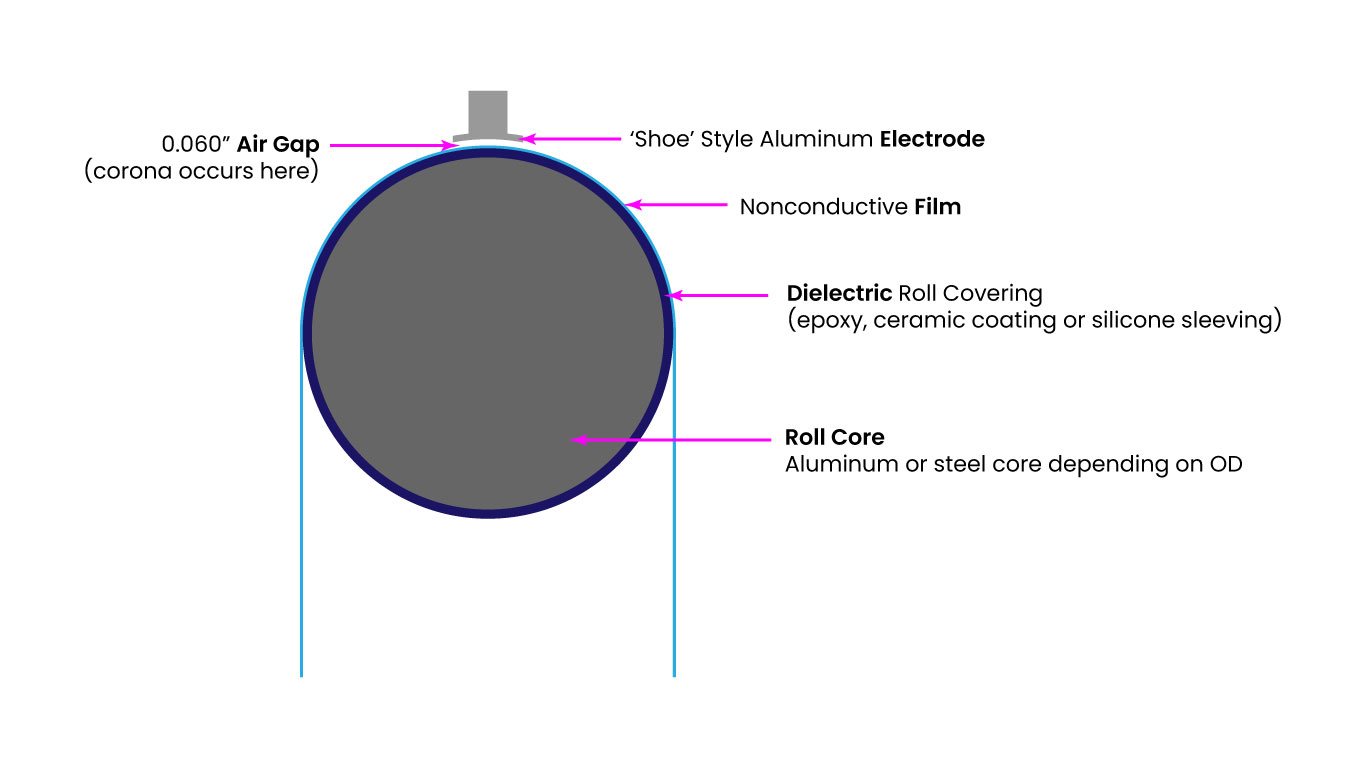

There are four essential components of a corona treater: first, the high-voltage generator. The function of the high-voltage generator is to maintain a constant output power at a set level when delivering voltage to the electrode. Next, the electrode delivers the high voltage to the air gap above the ground roll and spreads the energy across the web. To produce corona discharge (e.g., ionized air), both a high voltage potential and a ground potential are needed. Usually, the grounded roller serves as the ground. Finally, the buffer dielectric. This can be located on the ground roller or above it (the buffer dielectric can also be the electrode). The role of the buffer dielectric is to limit the current flow. Below is a diagram breaking down the key components of a covered roll corona treater (Figure 1).

Measuring Corona Dosage with Watt Density

Watt density is a fundamental formula in corona treatment. It represents the power delivered to the substrate per unit area and is affected by the power output of the treater, the width of the electrode, line speed, and number of treat sides (1 or 2). Increasing watt density increases polar group density, thus raising the surface energy [1][10].

Watt density ((watts) / ft²/min) = (Power (watts)) / (Treat Width (ft)*Line Speed (fpm)*Treat Sides (1 or 2))

Establishing a Target Surface Energy

Adequate adhesion starts with wetting: when a liquid spreads uniformly across a surface, it can make contact, anchor, and bond. In general, the target surface energy of the substrate should be 8-10 mN/m higher than the surface tension of the ink, adhesive, or coating to ensure adequate wetting and adhesion [2]. However, this difference does not always guarantee successful bonding. To establish a target surface energy, it is helpful to know the surface tension of the liquid to be applied.

It is essential to recognize that each application has specific surface energy requirements. For instance, in printing, solvent-based inks require a lower surface energy than water-based inks due to the inherently higher surface tension of water (72.8 mN/m). The water raises the surface tension of the ink above that of solvent-based alternatives. Because each ink formulation has unique characteristics, printers must carefully match the substrate’s surface energy to a compatible level of the surface tension of the specific ink [2]. The same principle applies to other adhesion-dependent processes, such as coating and lamination.

Measuring Surface Energy

Dyne Testing

Dyne testing is a pass/fail assessment used to evaluate whether the liquid of a known surface tension can wet a surface, serving as an indirect measure of surface energy. Due to its simplicity and speed, dyne solutions have become a standard in production environments. However, dyne testing comes with significant limitations. It does not provide information about the polar and dispersive components (critical factors in the accuracy of surface energy), and results are often subjective, relying on visual interpretation by the operator [2][7][8]. Furthermore, the ASTM D2578 standard for dyne testing outlines the use of dyne solutions for measuring wetting tension of nonporous polyethylene and polypropylene films. Its use on substrates not defined in the ASTM standard can lead to inaccurate conclusions [9]. It is essential to ensure material compatibility with the test method before drawing conclusions from dyne data. Moreover, dyne solutions/pens are also highly susceptible to contamination from environmental factors. Improper execution, such as double-dipping applicators or using dyne pens incorrectly, further impairs reliability.

While convenient, dyne solutions cannot provide quantitative readings and are not suitable for troubleshooting or high-accuracy environments. Dyne solutions are solvent-based and may cut through surface contaminants or migrated additives, such as slip agents, creating false positives. In this case, a film may pass dyne testing but still fail in downstream adhesion processes, as confirmed in studies where a film with excess slip additives exhibited good dyne readings but ultimately failed to bond [4].

Contact Angle Measurement

Contact angle measurements offer more profound insight into the substrate’s surface chemistry by analyzing how a liquid droplet interacts with the surface. The angle formed between the droplet and substrate (known as the contact angle) helps to calculate the surface free energy (mN/m) using models such as Owens, Wendt, Rabel, and Kaelble (OWRK), which separate the energy into polar and dispersive components. See figure 2.

Liquid surface tension is different than solid surface energy, but they are often treated as equal [1][2]. It’s important to note that the calculated surface energy can vary depending on the test liquids and the analytical model used. The OWRK model is standard and well-suited for polymers.

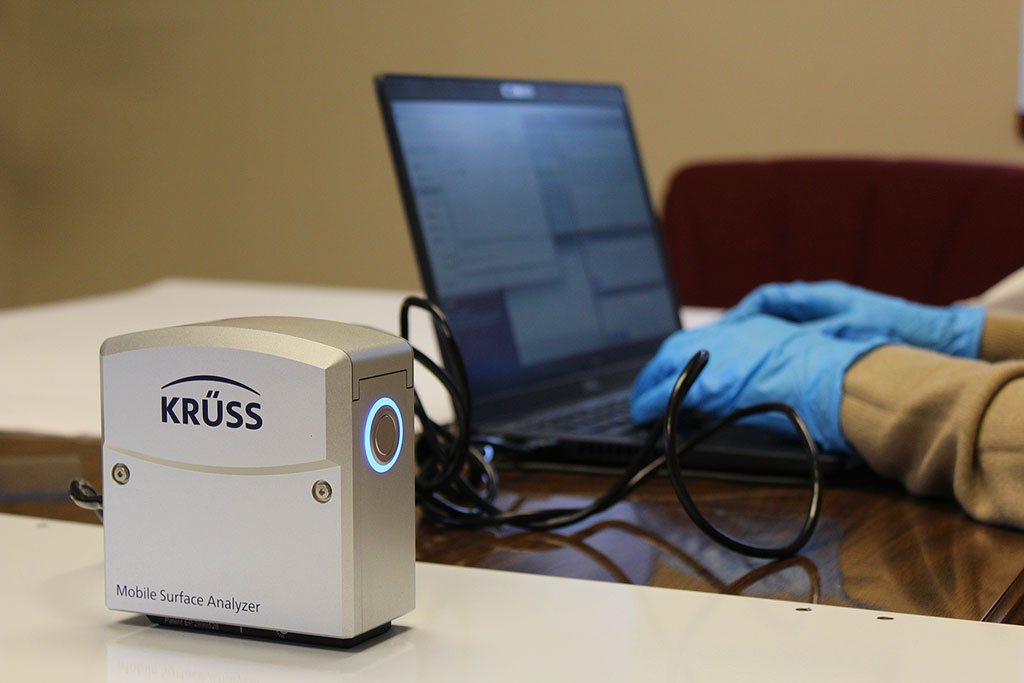

Instruments like the KRÜSS MSA (figure 3) automate this process by dispensing small droplets, typically water (polar) and diiodomethane (non-polar), onto the surface. The device captures the droplet shape and measures the contact angles of both liquids for several seconds. Then, the device calculates the surface free energy with high accuracy and repeatability.

| Method | What It Tells You | When to Use It |

|---|---|---|

| Dyne Solution | If a liquid of a known surface tension wets the surface, it is possible to estimate the surface energy of the solid. | Quick on-the-fly QA on nonporous polyolefins. |

| Contact Angle | Measures the actual surface energy, including polar/dispersive breakdown. | Use on complex engineered films, coated materials, or when adhesion fails unexpectedly. |

Common Pitfalls of Corona Treatment

Over-treatment

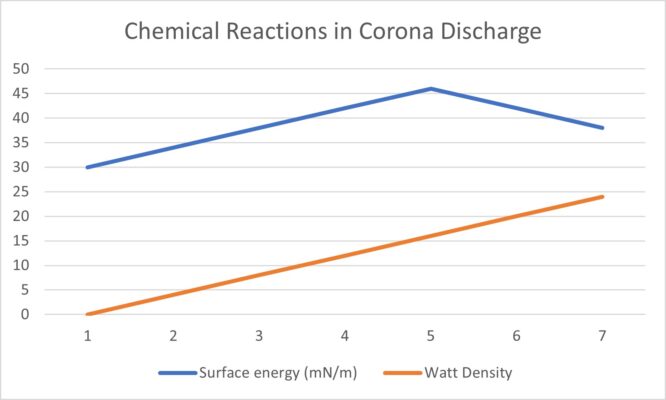

Two types of chemical reactions can happen in corona discharge. The first is a fast reaction and is the key to enhanced wettability; it is what makes corona treatment a successful solution to adhesion problems. This reaction forms carbonyl, carboxyl, and hydroxyl groups on the surface [1][10]. These are highly polar groups that increase the surface energy. The second, slower-speed reaction is the conversion of carbonyl groups into ether groups. This reaction is detrimental to treatment; ether groups are non-polar and tend to lower surface tension [1]. Thus, there is a ‘perfect medium’ in corona treatment. Treat with too much power, and you risk introducing a contradictory reaction, reversing the wettability and printability introduced by corona treatment’s initial reaction. If the second reaction occurs, the surface energy increases will stagnate, and gradually begin to decrease as more power is applied. Converters should monitor treatment to ensure the use of a proper watt density to reach the target surface energy while avoiding over-treatment. Figure 4 illustrates an example of crossing into the threshold of overtreatment. Remember that all materials treat differently, and this threshold is different for every substrate.

Additives

Additives like stabilizers and slip agents can affect the oxidation chemistry of the corona treatment process. Once corona treated, the substrate’s surface is at a higher surface energy than its surroundings. Film additives migrate to the high-energy surface, reducing the surface energy of these areas. This repositioning or rearranging of the molecular structure also causes the corona treatment to decay faster than a substrate that lacks these additives [1]. Thus, decreasing the amount of time a converter can print or adhere to the corona-treated film.

Slip additives are particularly detrimental to the wettability of films. As slip concentration increases, treatment efficiency decreases. Thus, higher concentrations of slip additives require higher watt densities when compared to materials with lower concentrations of slip. Depending on the application’s requirements, extruders can establish a balance between the amount of slip additives and corona dosage [1].

Degradation of Corona Treatment

The most significant cause of corona treatment decay is additive migration. The higher the initial treatment dosage, the greater the amount of degradation the substrate is prone to experience [1]. In addition to additive migration, several factors can cause premature degradation, including the amount of time since treatment, treatment level, substrate type, presence of additives, roll tightness, handling and storage conditions, temperature, and humidity.

To avoid decay and additive migration, corona treaters are typically placed in-line directly before the printing, coating, or laminating process. This ensures that the treated surface is at peak surface energy, maximizing adhesion results.

“Bump” Corona Treatment

Bump treating is the process of re-treating film that was originally treated at the point of extrusion, immediately before the adhesion process. Because the surface has already been modified, bump treaters operate at lower power levels as the substrate requires a lower watt density than the initial treatment. Studies show that bump-treated films exhibit higher oxygen content at the same measured surface energy compared to freshly treated films, and this additional oxygen is especially beneficial for bonding with water-based inks [1][10].

Converters purchasing pre-treated film should install a bump treater on the converting line directly before adhesion. For companies that both extrude and convert, one treater can be installed on the blown film tower for initial treatment, with a second, lower-output treater placed directly before adhesion. For extrusion-only operations, the treater is typically positioned on the blown film tower, as films treated at higher relative humidity levels have been shown to treat more efficiently [1].

Conclusion

By understanding the characteristics of liquids and solids and how they relate to adhesion, selecting the proper testing method, and avoiding the common pitfalls listed, converters can minimize failures, improve efficiency, and achieve stronger, more durable bonds.

About the Author

Alyxandria Klein is the Marketing and Sales Director at QC Electronics. Raised in the industry under the mentorship of her father, Ken Klein, Aly combines hands-on experience with a growing expertise in surface science. Her technical journey began five years ago with a KRÜSS MSA. Learning about surface energies and what makes a good bond sparked a desire to help people understand their materials better. Aly is currently pursuing a business degree at the University of Wisconsin–Madison. She continues to study materials science independently, driven by a passion to make adhesion principles accessible to manufacturers. She is a member of FTA, GBIG, and PMMI.

Contact Aly

Email: aklein@qcelectronics.com

Phone: +1 608 742 1262

Connect with Aly on LinkedIn: Alyxandria Klein | LinkedIn

Bibliography

[1] Sun, C. (Q.), Zhang, D., & Wadsworth, L. C. (1999). Corona treatment of polyolefin films—A review. Advances in Polymer Technology, 18(2), 171–180. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1098-2329(199922)18:2<171::AID-ADV6>3.0.CO;2-8

[2] Aydemir, C., Altay, B. N., & Akyol, M. (2021). Surface analysis of polymer films for wettability and ink adhesion. Color Research & Application, 46(3), 489–499. https://doi.org/10.1002/col.22579

[3] ASTM International. (2004). ASTM D5946-04: Standard test method for corona-treated polymer films using water contact angle measurements. https://www.astm.org/d5946-04.html

[4] Brighton Science. (2020, June). The dangers of missing vital surface quality information in production. https://www.brighton-science.com/blog/the-dangers-of-missing-vital-surface-quality-information-in-production

[5] Kundt, M. (2011). Surface treatment of materials for adhesive bonding. John Wiley & Sons.

[6] Izdebska, J. (2016). Corona treatment. In Printing on polymers (pp. 123–142). William Andrew Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-323-37468-2.00008-7

[7] Krüss GmbH. (n.d.). Contact angle and surface energy – Dyne inks and their limitations. https://www.kruss-scientific.com

[8] Strobel, M., & Lyons, C. S. (2011). An essay on contact angle measurements. Plasma Processes and Polymers, 8(1), 8–13. https://doi.org/10.1002/ppap.201000041

[9] ASTM International. (2017). ASTM D2578-17: Standard test method for wetting tension of polyethylene and polypropylene films. https://www.astm.org/d2578-17.html

[10] Ebnesajjad, S., & Landrock, A. H. (2021). Adhesives technology handbook (3rd ed.). William Andrew Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-323-35595-7.00001-2